History

In October 1872, 19 members of the first American North Pole Expedition abandons ship when it appears that their ship, the Polaris, would be crushed by ice. However, the ship floats away leaving more than half the expedition stranded on an ice floe. Six months later, they are rescued from their floating ice camp off the coast of Newfoundland. The American government immediately sends out a search mission for the Polaris and its remaining crew. American Navy Lt. Wm. Mintzer, who is part of the rescue mission, discovers mica on Baffin Island, and subsequently applies to the British government for a land grant to carry out mining operations there. This prompts Britain’s decision to transfer its holdings in the Arctic to Canada.

The transfer of the Arctic takes six years. During this time several expeditions to the region are carried out, including the British Nares’ North Pole expedition, 1875-76, and the failed American North Pole expedition aboard the Jeannette in 1879. The Arctic Archipelago is officially transferred to Canada in the summer of 1880. Between 1881 and 1883, British, German and American teams set up scientific stations in Canada’s Arctic for the First International Polar Year. The American expedition, led by Lt. Adolphus Greely, ends tragically in the deaths of 19 of the 25 men.

Hudson’s Bay Expedition of 1884:

In the early 1880s, Prairie farmers, fed up with the poor deal they are getting from the Canadian Pacific Railway monopoly, vow to find a better route to transport their grain to European markets. A route through Hudson Bay and Hudson Strait to the Atlantic Ocean seems the most feasible. In 1884, the Dominion government agrees to finance a three-year study of this Hudson Bay Route to determine the length of time that such a route will be relatively ice-free for shipping purposes. During the three summer expeditions, Churchill and Nelson will also be assessed to determine a location for a shipping port for a railway to be built to.

The first expedition to Canada’s Subarctic, commanded by hydrographic surveyor Lt. A.R. Gordon is organized. The expedition travels through Hudson Strait and across Hudson Bay to Churchill. It establishes six observation stations at points along the north and south sides of Hudson Strait and 19 men were left at these stations to carry out research and meteorological studies for the next year.

Hudson’s Bay Expedition of 1885:

Lt. Gordon commands the second expedition to Hudson Strait aboard the Royal Navy ship Alert. The expedition again will pass through Hudson Strait and across Hudson Bay to survey ports at Churchill and Nelson rivers to better assess an ideal shipping port. That summer’s passage of the Strait is a difficult one and the heavy ice damages the ship. One station is closed, 15 new scientists are left at the remaining five stations, and the first year’s station men are returned south in September.

Hudson’s Bay Expedition of 1886:

In 1886, Gordon leads the third and final expedition through the Hudson Bay Route. It is not an easy voyage. Heavy ice impedes their progress on the western passage through the Strait. On the return journey, the observation stations are dismantled and the building materials, remaining provisions, and station men are taken onboard and returned to Halifax. Gordon’s subsequent final official report is cautious, saying the route is navigable for no more than four months a year. Gordon’s reports are shelved and development of the Hudson Bay Route stalls.

Expedition to Hudson Bay and Cumberland Gulf, 1897:

In 1897, the Dominion government once again considers the potential of a Hudson Bay Route. At the end of May, an expedition is sent out to determine the length of time that Hudson Strait would be navigable for shipping purposes. Dr. William Wakeham commands the expedition to Hudson Strait with two teams from the Geological Survey of Canada, which are dropped off on the north and south shores of Hudson Strait to carry out geological studies. Wakeham also heads to Cumberland Sound where whalers have operated since the 1840s. Here he raises the flag on Kekerten Island, making the first official Canadian claim of Arctic sovereignty. Wakeham’s expedition makes six passes through Hudson Strait before returning to Nova Scotia in November. He puts the length of time the route is passable as just two weeks longer than Gordon.

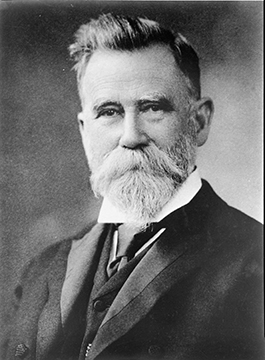

Capt. Joseph-Elzéar Bernier:

In April 1871, a young Capt. Bernier visits the sailing-steamship Polaris at the navy yard docks in Washington, D.C., that is being partially fitted for its North Pole expedition. Bernier is not convinced of its Arctic seaworthiness. His assessment of the vessel is proven right when, in May 1873, reports of the ship’s demise and the 19 survivors plucked from the ice floe makes headlines.

This disaster leads Bernier to study Arctic navigation. For him, the Polaris is the beginning of a life-long passion for the Arctic. In February 1895, Bernier accepts the position of governor of the Québec gaol, welcoming the opportunity to rest his sea legs and pursue his passion – the Arctic. He spends hours in his office, studying every Arctic-related book and chart of Arctic waters that he can get his hands on. Reading these English explorers’ accounts is an accomplishment for a Francophone with a Grade 6 education.

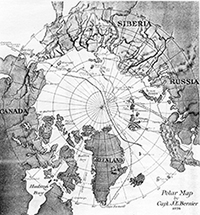

Bernier firmly believes that the prize of the North Pole belongs to Canada. Attaining the Pole would, in the eyes of the rest of the world, secure all the land between that point at 90°N and the rest of the mainland for Canada. Bernier devises a plan for a polar expedition based on Fridtjof Nansen’s 1893-96 use of the polar ice drift in his attempt to make the Pole.

One Saturday night in December 1897, Bernier lectures before the Quebec Geographical Society on his proposed polar expedition, using his impressive new wall-sized map, drawn by one of the gaol’s prisoners, doing time for forgery. He gains the unanimous support of the Geographical Society. Its president, Maj. Nazaire LeVasseur, petitions people well-connected in Québec society and politics for funding for Bernier’s project. In February 1898, LeVasseur writes a letter of introduction to Prime Minister Laurier. Bernier follows up with a letter to Laurier, laying out his plan for a North Pole expedition in a twenty-paged report neatly handwritten, oddly enough, in English.

Bernier receives a polite thank you note from the prime minister, suggesting he seek other financial support before approaching the government. For five years, Bernier petitions private investors, the general public, and the federal government for financial support for his North Pole Expedition.

Expedition to Hudson Bay and the Arctic Islands, 1903-04:

In 1903, foreign activity in the North and the possibility of claims to the region, spur the Canadian government to organize two northern expeditions. One expedition of two police officers heads to Herschel Island north of the Yukon where whalers have been operating unimpeded, to set up a police post. The second expedition, led by Albert P. Low of the Geological Survey of Canada, heads to Hudson Bay to intercept American whalers operating there. The expedition includes five Northwest Mounted Policemen (NWMP) and their commander, Maj. J.D. Moodie. The expedition is the first Canadian expedition to overwinter in the North.

The Neptune expedition passes an eventful winter, frozen in Fullerton Harbour in north western Hudson Bay near the American whaling ship Era. The NWMP establish the first police post on Hudson Bay, creating ‘M’ Division. The assistant doctor goes insane and dies, the cabin boy wanders off in a snowstorm; and one American sailor dies of scurvy. When the ice begins to break up in June, the American Capt. Comer, his crew and Inuit employees head out whaling. Low and six of his men accompany Comer as far as Southampton Island to carry out scientific studies. Low also raises the flag on Southampton and makes a proclamation of sovereignty.

Expedition to Hudson Bay and Northern Waters, 1904-05:

Capt. Bernier fails to raise enough private funds to finance his North Pole expedition, and the federal government does not offer financial support. Trouble arises over the Alaskan/Yukon boundary and a dispute is settled in the United States’ favour in October 1903.

The Dominion government decides another northern expedition is necessary to assert its authority in the North, and hires Bernier to find a suitable ship. Bernier purchases the German ship Gauss, rechristens it Arctic, and outfits it for a three-year northern expedition. Meanwhile, Low’s expedition departs Fullerton and heads east. Maj. Moodie leaves the expedition at Port Burwell in August 1904 to return to Ottawa to report on activities in Hudson Bay. The Neptune heads north into the Arctic Archipelago and Low begins to claim the islands for Canada.

Moodie is given command of the Arctic, which becomes a Northwest Mounted Police patrol ship heading to Hudson Bay. Bernier’s hopes of a North Pole expedition are dashed. But the greatest humiliation is that he is relegated to sailing master.

The Arctic finally heads north up the Labrador coast to Hudson Strait. It arrives in Fullerton Harbour on western Hudson Bay, and anchors for the winter near the American whaler Era. Moodie is accompanied by ten mounted policemen, as well as his wife and their twenty-year-old son. The barracks onshore are expanded to accommodate the enlarged police force.

In the summer of 1905, The Arctic leaves Fullerton to continue Low’s work of claiming the Arctic islands. Maj. Moodie decides to pick a location in Hudson Strait for another police post. The expedition spends six weeks waiting for the supply ship, and so fails to continue north into the islands. The expedition finally heads south that fall.

Expedition to Arctic Islands and the Hudson Strait, 1906-07:

In 1906, the Dominion Government decides that a regular patrol of its Arctic Islands is required and hires Capt. Bernier to command the first expeditions. He is also requested to claim the Arctic islands for Canada. That spring there is an inquiry into the supplies purchased for the Arctic in 1904. Allegations of a “rake-off” are unfounded and the Arctic expedition goes ahead as planned in the summer of 1906. After claiming a number of islands for Canada, Bernier decides to spend the winter at Pond Inlet. When the ice melts, Bernier continues his task of raising the flag on more islands, before returning to Quebec City in mid-October.

Expedition to the Arctic Islands and Hudson Strait, 1908-09:

In 1908, the Liberal government approves another cruise to the Arctic for sovereignty reasons. Bernier is given command of his third expedition. The expedition claims more islands before preparing to overwinter in Winter Harbour on Melville Island in the High Western Arctic. The ship passes an uneventful winter. On Dominion Day, July 1, 1909, in a ceremony at Winter Harbour’s historic Parry’s Rock, Bernier makes a sweeping proclamation and claims the entire Arctic Archipelago for Canada. The expedition returns south and Bernier is welcomed as a hero.

That spring, Lt. Robert Peary and Dr. Frederick Cook both publicly claim to have attained the North Pole. In the end, Bernier’s contribution to Arctic sovereignty is of more value to Canada than any expedition to the North Pole could have been.

Expedition to the Arctic Islands and Hudson Strait, 1910-11:

Bernier leads his fourth government expedition north in 1910. His goal is to make the Northwest Passage. It is clogged with ice, however, and he retreats to Arctic Bay on northwest Baffin Island where they overwinter. His men make a number of geological expeditions over the winter. The geologist, Lavoie, makes extensive sled voyages to survey the Foxe Peninsula on the west side of Baffin Island, until he was severely injured by an exploding gas can. The expedition returns south to find the government has changed and Arctic exploration is no longer a priority.

1912:

No government patrol is sent to the Arctic in the summer of 1912. The Hudson Bay Railway idea is revived once again, and the government orders surveys of Hudson Bay and Strait in the summers of 1910, 1911, and 1912. The Arctic is used for the magnetic survey of 1912, before being relegated to lightship in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Bernier retires from his civil duties and goes into the Arctic fur trading/shipping business in Pond Inlet.

Photo credits: The many outstanding archival photographs posted on this website are reproduced with permission from: the Library and Archives of Canada (LAC), Natural Resources Canada 2013, courtesy of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC), Parks Canada, and the RCMP Historical Unit, “Depot” Division (RCMP).

Parry’s Rock on Melville Island. The datum rod was placed on top of the rock by Walter Erastus Weddell Jackson, the meteorologist on Bernier’s 1908-09 expedition. Bernier had his signature beaver attached to the rod with Arctic engraved on it. On the left side of the rock is the plaque Bernier had bolted to it, claiming the entire Arctic for Canada. [Photo is taken from

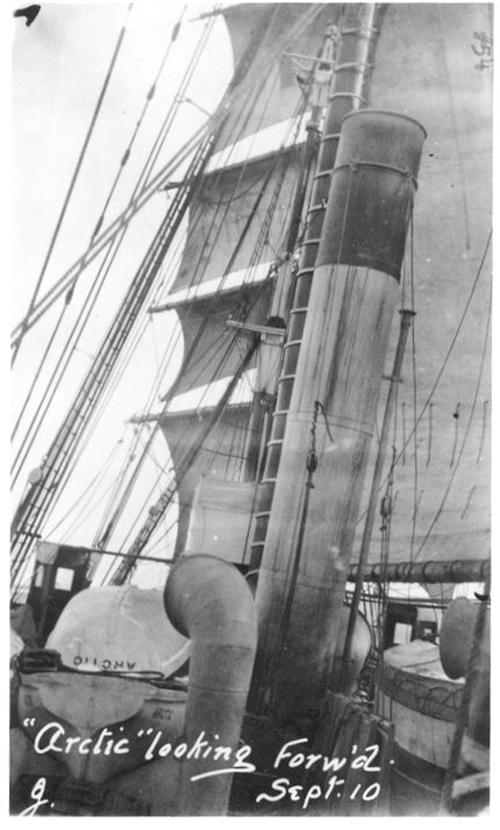

Parry’s Rock on Melville Island. The datum rod was placed on top of the rock by Walter Erastus Weddell Jackson, the meteorologist on Bernier’s 1908-09 expedition. Bernier had his signature beaver attached to the rod with Arctic engraved on it. On the left side of the rock is the plaque Bernier had bolted to it, claiming the entire Arctic for Canada. [Photo is taken from  The Arctic at Port Burwell, 1907. [LAC, PA-096482]

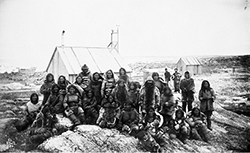

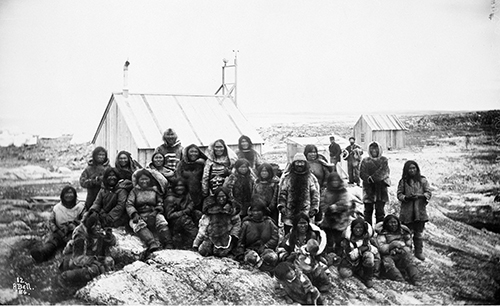

The Arctic at Port Burwell, 1907. [LAC, PA-096482] Geraldine was the 50-year-old wife of Inspector J.D. Moodie and a professional photographer. She had operated three photographic studios on the Prairies: in Medicine Hat Alberta, Battleford, Saskatchewan, and another in Maple Creek, Saskatchewan. She accompanied her husband on his second trip to Fullerton Harbour and lived the year at the detachment on short. She set up a studio at the mounted police post at Fullerton Harbour and photographed many of the local people. Her subjects are carefully posed with a canvas backdrop in front of which the women, children, and men stood or sat. As well, she used artificial studio-type lighting. She became acquainted with the local Inuit, forming relationships and friendships with the women that are apparent as they appear relaxed and comfortable in her photographs. Her photos capture the dignity and essence of each person. [Parks Canada, 0696-0009, photographer- G. Moodie]

Geraldine was the 50-year-old wife of Inspector J.D. Moodie and a professional photographer. She had operated three photographic studios on the Prairies: in Medicine Hat Alberta, Battleford, Saskatchewan, and another in Maple Creek, Saskatchewan. She accompanied her husband on his second trip to Fullerton Harbour and lived the year at the detachment on short. She set up a studio at the mounted police post at Fullerton Harbour and photographed many of the local people. Her subjects are carefully posed with a canvas backdrop in front of which the women, children, and men stood or sat. As well, she used artificial studio-type lighting. She became acquainted with the local Inuit, forming relationships and friendships with the women that are apparent as they appear relaxed and comfortable in her photographs. Her photos capture the dignity and essence of each person. [Parks Canada, 0696-0009, photographer- G. Moodie] The

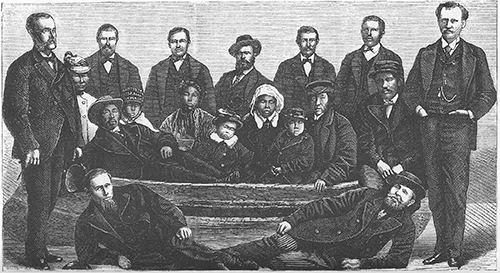

The  Meeting of the Alaska Boundary Tribunal, Foreign Office, London, England, October 1903.

Meeting of the Alaska Boundary Tribunal, Foreign Office, London, England, October 1903. The Neptune and Era at Fullerton Harbour

The Neptune and Era at Fullerton Harbour Herschel Island is a thirty-five square mile, treeless island, three miles off the Yukon coast and northeast of the Alaska boundary. It offered American whalers an ideal winter haven to carry out their profitable whaling industry. They paid no tariffs and had no whaling licences. Pauline Cove, on the southeast side of Herschel, offered a natural harbour, deep enough for the large whaling steamships to anchor in, protected from the northerly winds and drifting ice pack. Here, the American whalers built warehouses and dwellings, and by 1892-93 there were 160 whalers living year-round at Pauline Cove. The Northwest Mounted Police set up a post on Herschel to monitor the whalers’ activities in August 1903. [RCMP 1987.126.26]

Herschel Island is a thirty-five square mile, treeless island, three miles off the Yukon coast and northeast of the Alaska boundary. It offered American whalers an ideal winter haven to carry out their profitable whaling industry. They paid no tariffs and had no whaling licences. Pauline Cove, on the southeast side of Herschel, offered a natural harbour, deep enough for the large whaling steamships to anchor in, protected from the northerly winds and drifting ice pack. Here, the American whalers built warehouses and dwellings, and by 1892-93 there were 160 whalers living year-round at Pauline Cove. The Northwest Mounted Police set up a post on Herschel to monitor the whalers’ activities in August 1903. [RCMP 1987.126.26] Bernier’s calling card, 1898

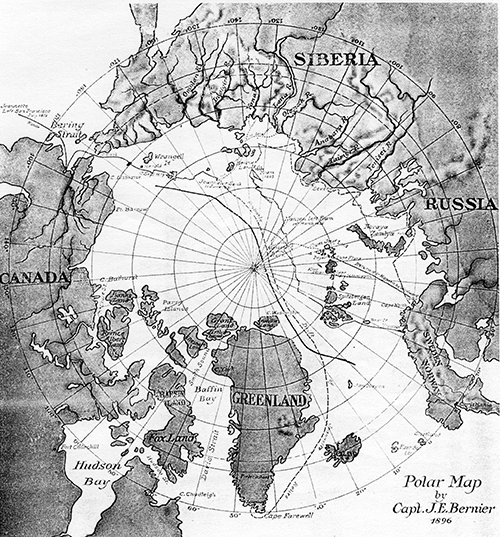

Bernier’s calling card, 1898 Forger Map

Forger Map Capt. Bernier in his cabin aboard the

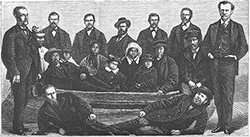

Capt. Bernier in his cabin aboard the  Officers of the Alert, 1885

Officers of the Alert, 1885 Inuit at Stupart Bay

Inuit at Stupart Bay The

The