Observation Stations

Station Observers and Observations:

Six men were chosen as station observers for the stations erected along Hudson Strait. Thirteen other men acted as station men. Two men would stay with each head observer from one summer to the next. These men were all under thirty and unmarried. They had signed up for a year of adventure in the name of science. The men were engaged at a rate of $35 per month, with an additional four dollars per week as board money during the voyage.

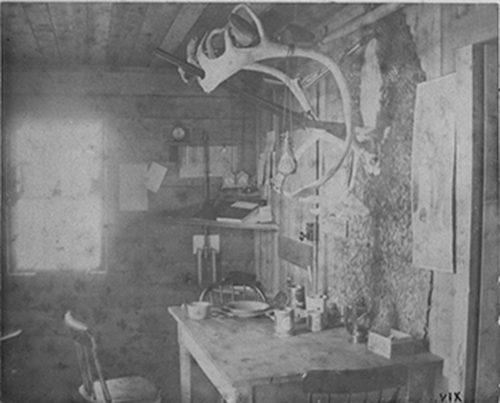

Gordon's 1884 instructions for the officers in charge of the stations were as follows: “As the primary object of the whole expedition is to ascertain for what period of the year the Straits are navigable, all attention is to be paid to the formation, breaking up and movements of the ice.” Each station was provided with a sundial and timepiece, and the clock was to be tested at noon each day when there was sunshine. Daily temperature, barometric pressure, tidal observations, and weather conditions were all to be noted in detail. Also, remarks about the movements of birds, fish, and any other wildlife, as well as grasses or other flora were to be recorded.

The men were instructed to take every precaution against fire: “Two buckets full of water are always to be kept ready for instant use.” Each station was equipped with a boat with the understanding that no one was to travel farther from the station than they could return from in the same day.

Instructions on health were also given, “As the successful carrying out of the observations will, in a great measure, depend on the health of the party, the need of exercise is strongly insisted on during the winter months, and also that each member of the party shall partake freely of the lime juice supplied.” The hazards of living in the North during the dark winter months had long been recognized by Arctic adventurers, and the government was taking every precaution to ensure the welfare of its men.

Station Supplies:

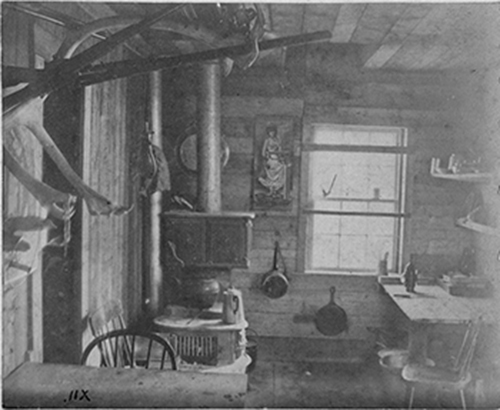

The Neptune which headed to Hudson Strait in 1884, carried aboard the lumber and sections of the prefabricated buildings constructed in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, that would be used for the observation stations. As well, 180 pound sacks of hard coal equalling twenty tons were also stowed on-board to be deposited at the observation stations for use in their stoves. Barrels of pork, beef, sugar, oatmeal, sacks of flour, soap, bags of bread, canned mutton, evaporated vegetables, including turnips and potatoes, apples, syrup, butter, cases of kerosene for the lamps, kegs of vinegar, tins of mustard, coffee, lime juice, beans, canned peaches and pears, currants, and boxes of cocoa were earmarked for the stations. In short, everything the men would need to live for up to eighteen months – everything, that is, but fresh meat and vegetables.

Station Buildings:

Station Buildings:

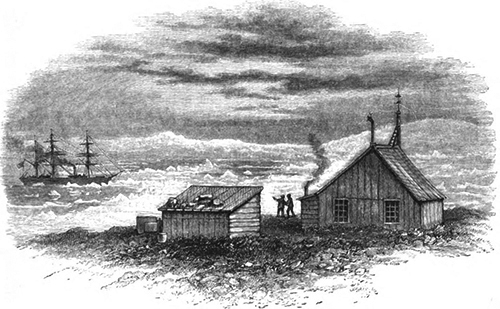

In a March 1885 article published in Science magazine, Col. William P. Anderson, a hydrographic surveyor with the Department of Marine and Fisheries, described the station buildings erected along the Hudson Strait in 1884. Anderson became a renowned lighthouse architect at the turn of the century, designing and building about 335 lighthouses across the country by 1904. He was not a member of the expedition, but as he had an intimate knowledge of the construction of the houses, it is very likely that he was the architect of the observation station buildings.

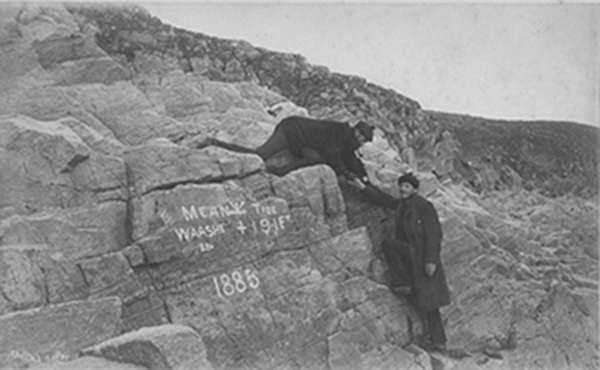

Anderson noted that each “hut” was 16 by 20 feet, and divided into three rooms with a porch. The buildings “had double walls of board, with an outer and inner air-space formed by a sheathing of tarred paper.” It was recommended after construction that the men should collect sod to cover the house “to further protect it from cold,” and, at the onset of winter, pack snow over the whole thing for extra insulation. This was sage advice, except that most of the ground the buildings were erected on was rocky with no insulating sod to be found within a hundred miles. The men did attempt to pack snow around the houses, though.

Observation Stations were erected at:

~ Port Burwell on Cape Chidley, a tiny island off northern Labrador at the southern entrance to Hudson Strait.

~ Ashe Inlet on Big Island on the north side of Hudson Strait.

~ Stupart Bay on the south side of Hudson Strait.

~ Port Laperrière on Digges Island south of Nottingham at the entrance to Hudson Bay.

~ Port De Boucherville on rocky Nottingham Island, at the north entrance to Hudson Bay on the western end of Hudson Strait.

~ Skynner’s Cove on Nachvak Bay, north eastern Labrador. This was the only station not erected along Hudson Strait.

Photo credits: The many outstanding archival photographs posted on this website are reproduced with permission from: the Library and Archives of Canada (LAC), Natural Resources Canada 2013, courtesy of the Geological Survey of Canada (GSC), Parks Canada, and the RCMP Historical Unit, “Depot” Division (RCMP).